Beyond the Bronze’ explores the realities of the public art process, from artist selection to community involvement, revealing the hidden dynamics that shape public space through art.

by Iryna Kanishcheva and Oaklianna Caraballo

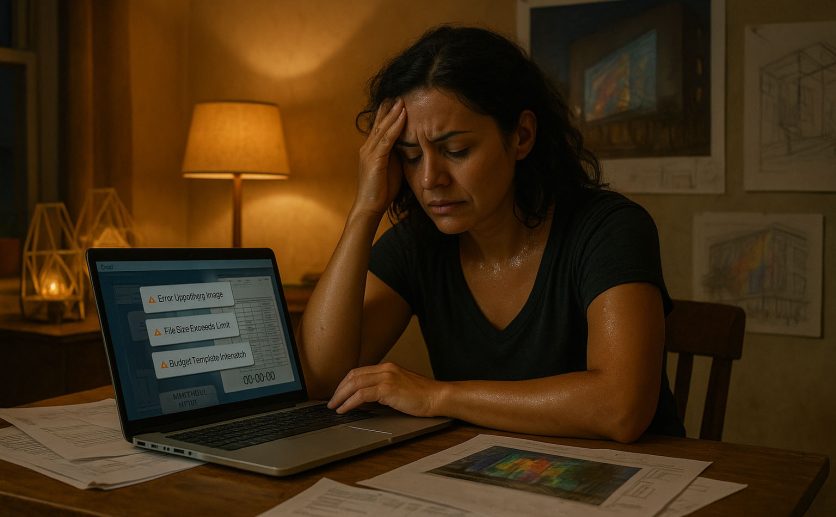

Multimedia artist Rochelle Pérez closes her laptop with a sigh. She has just abandoned yet another public‑art application. The portal rejected her images for being over the size limit; the budget template didn’t match her projection project; it wasn’t clear if they would accept a technology-based project; and the countdown timer hit zero before she could even post a question. She had waited until the last day, juggling a private commission and trying to apply for other calls. Rochelle is no novice — her award‑winning light pieces animate walls from Miami to Montréal—but the fragmented machinery of public‑art procurement has worn her down. Somewhere, a municipal panel will convene without seeing her idea, and a community will never experience the animated mural but a traditional one instead.

Rochelle’s story is not exceptional. It is the predictable by‑product of a system whose structures—RFP rules, jury composition, digital platforms, and other mandates in the public art process — quietly select artworks long before any aesthetic debate begins. This article unpacks that machinery, tracing how procedural choices ripple outward to shape what gets built, whose voices are heard, and how communities experience the art that rises from their sidewalks.

The Funding Formula Shapes the Art

“Back in the 1980s I could pick up the phone and a local bank or insurance company would write the whole check—corporate civic pride paid for half our collection,” Barbara Hill recalled during our interview. That simple observation still holds: who pays for a project quietly dictates everything from the paperwork you file to the kind of artwork that survives the review cycle. Artistic “fit” shifts: Public agencies prioritize cultural representation when navigating the public art process; CRAs want visible economic uplift; private developers chase share‑able visual impact; new federal directives reward patriotic statuary.

Percent‑for‑Art programs were born in the United States in the 1960s, formalizing an idea that public space deserves public beauty. Their offspring now span every scale—from the federal General Services Administration to tiny beach towns. Parallel to these programs, developer‑driven placemaking has exploded: luxury towers and corporate campuses hire curators or design firms to install Instagram‑ready icons that telegraph brand values. Layered onto both are temporary initiatives: light festivals, tactical urbanism pop‑ups, artist residencies that test ideas quickly.

| Funder | Typical mechanism | What it buys you | What it demands |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percent‑for‑Art ordinances (0.5 – 2 % of capital budgets) | Automatically skims construction dollars (e.g., the U.S. GSA reserves 0.5 %) | Long‑term, permanent works integrated with infrastructure | Rigid procurement rules, multi‑year reporting, public design reviews |

| Public grants (NEA, State & Local Arts Agencies) | Competitive grants—$2.28 B total public arts funding in FY 2023 | Pilot programs, social‑impact art, operating support | Quantitative outcomes, equity metrics, multi‑layer audits |

| Corporate & foundation giving (~30 % of nonprofit arts revenue) | CSR budgets, naming gifts, cause marketing | Fast‑tracked commissions that reinforce brand values | Quarterly ROI decks, image control, short revision windows |

| Developer‑driven placemaking | Private project budgets, art allowances, voluntary fees | Landmark “Instagram moments,” amenity art | Architect‑led design charrettes, tight construction schedules, legal risk management |

The policy weather matters. In 2024 Florida wiped out its entire state arts‑and‑culture grant pool — defunding scores of experimental projects — and redirected tourism dollars toward more “traditional” commemorative pieces. Then, in April 2025, the White House siphoned $34 million from the NEA and NEH to commission 250 marble‑and‑bronze statues for the proposed National Garden of American Heroes. Finally, the FY 2026 “skinny budget” sent to Congress in May 2025 seeks to zero out the NEA, NEH, IMLS, and CPB altogether while boosting defense spending.

Together, these moves shift public funding away from innovative, future‑facing projects toward traditional figurative monuments—exactly the kind of “bronze over innovation” realignment Barbara warned would calcify the field: “As soon as a committee member with zero arts background—a schoolteacher—insisted on bronze busts of famous people, I threw up my hands. I just couldn’t do it; things were sliding from bad to worse.”

Process as Gatekeeper: Where Creativity Collides with Bureaucracy

Every public art commission begins with a document. The RFP and RFQ becomes the gatekeeper between intention and imagination. While these documents aim to ensure transparency, they often unintentionally create barriers that limit creative potential.

Artists are frequently asked to respond to detailed scopes of work without critical context. What, for example, qualifies as “durable”? Is a solar-powered light sculpture considered more or less permanent than powder-coated steel? Without definitions, artists (and the jurors) are forced to guess—and that guess can disqualify talanted innovators. Worse, many RFQs omit site images or conditions, asking for concepts before artists have even seen the environment their work must respond to.

The language itself is another obstacle. Many RFQs and agreements are written using templates from decades past, packed with outdated standards and broad clauses (like “community engagement plans”) that read as vague checklists rather than creative prompts. These documents rarely reflect new media or evolving practices, leaving digital artists, projection mappers, or XR designers struggling to fit into a mold made for stone and bronze. Clearly, the public art process needs improvements.

“One administrative challenge is time management because of the sheer volume of submissions. There are more applications than ever, and depending on the platform used, the text can be provided to jurors unformatted. Artist don’t always place required information first, leaving the burden on jurors to find it within a multipage document. These inefficiencies make verifying information difficult for the most dedicated juror.” – Oaklianna Caraballo.

The Economics of Applying: Opportunity Cost and Privilege

Preparing a public art proposal is often a micro‑grant of unpaid labor. For a mid-career sculptor, a single application can consume 30–40 hours. With success rates hovering around 5%, an artist may invest over 600 hours before securing one commission—a steep cost paid privately for a public good.

This arithmetic inherently privileges those with financial safety nets: savings, academic salaries, or steady commercial side gigs. Artists from underrepresented backgrounds, already navigating systemic inequities, are often the first to exit the process. In this way, the system quietly reinforces the very homogeneity that public agencies claim to combat through equity statements.

Artists often joke that they carry a “passport” of logins: Submittable for Florida, SmartSimple for San Francisco, state registries that require notarized signatures or physical mail-ins (read: extra expenses for artists). One portal asks for your name on every image; another will disqualify you if text appears at all. Most request the same materials—CV, work samples, statement—but in slightly different formats. Artists juggle PDFs, upload limits, and file naming conventions just to submit a portfolio—never mind that many portals still forbid video or interactive content, effectively excluding media artists from demonstrating movement, sound, or interactivity. Compounded across dozens of applications, these redundancies burn through hundreds of unpaid hours.

James Gabbert is sharing the story of his sculpture in Gainesville, FL.

The time-consuming application process also filters who gets to compete. A muralist with a ready portfolio and preexisting designs can respond to multiple 30-day calls with relative ease. In contrast, an artist working with robotics or interactive light must coordinate with engineers, research materials, and develop technical budgets, tasks that require more time and collaboration. Artists with administrative support can manage both creation and paperwork, while independent artists without help often fall behind. In the end, the system implicitly favors conventional practices and well-resourced applicants, sidelining artists whose work requires innovation, collaboration, and time. Now is a time for a more equitable public art process:

“We blend open calls with direct invitations to balance opportunity and excellence. Open calls democratize access, but direct invitations help us engage highly skilled artists who might not otherwise apply. We refine our criteria to ensure a fair and targeted process. For our private calls or curated projects, we issue an RFI—Request for Ideas—where artists briefly outline their concepts for a specific wall or space. This approach lets us directly assess an artist’s creativity and suitability for a project without being constrained by their previous experience. For instance, while it’s common for committees to prefer artists with specific experience, we’ve found that offering opportunities to those without exact experience often yields fresher, more innovative results.” – Iryna Kanishcheva.

Overlay all of this with inconsistent procurement rules: some cities embrace flexibility, others enforce rigid state-level protocols (e.g. discqualified if resume is missing). An artist may be celebrated in one region and blocked in another—not for artistic merit, but for mismatched procurement forms or eligibility checkboxes. Add to that the overly broad nature of many open calls—”all media considered” often still favors the familiar—and you end up with a system that pretends to be open, while subtly favoring safe, static, and already-proven models. The problem isn’t just bureaucracy—it’s that bureaucracy shapes aesthetics before the art even begins.

And for all this effort, the opportunity cost is staggering. Would an artist be better off spending hundreds of hours pursuing private commissions or commercial partnerships instead? Applying to public art calls can feel like buying endless lottery tickets—except you’re paying with time, not money.

Selection Committees: Human Bias Behind Closed Doors

The quintessential image of a public‑art jury is a conference table strewn with printouts, where arts commissioners and “community representatives” debate artist applications. Many panels are volunteer, convened just days before the deadline; some members skim PDFs on their phones between meetings.

Cognitive science tells us that rushed groups default to availability bias (favoring what is easiest to recall) and groupthink (aligning with the loudest voice). When panelists lack contemporary‑art expertise, they lean on personal taste or precedent—bronze busts feel safer than light sculptures. Even well‑intentioned diversity mandates can backfire if “community seats” go to individuals with no decision‑making power beyond optics.

Without transparency—few municipalities publish scoring breakdowns or provide feedback—artists cannot learn why they lost, and panels cannot audit their own patterns. Data that could expose systemic skew remains anecdotal.

“Success for us is not only about filling a call but ensuring the chosen artist’s work resonates with the community and achieves the project’s objectives. Beyond art that is selected, which is the most important aspect of success, I constantly evaluate my processes. Was the call clear? Were the finalists supported during the process? Does the art make sense? Is it well made?” – Oaklianna Caraballo.

Medium Bias: Permanence Over Innovation

Traditional procurement metrics—longevity, vandal‑resistance, maintenance projections—are optimized for permanent objects. Digital or ephemeral works score poorly: they are “hard to quantify,” “risk equipment failure,” “lack residual value.” Yet audiences under 35 increasingly seek interactive and time‑based experiences. When selection criteria valorize permanence, public art becomes a museum of materials rather than a living platform for new forms.

Cities that do embrace technology often do so cautiously. Smart‑lighting sculptures appear, but only if a vendor guarantees a 10‑year LED warranty. VR murals? Perhaps after a pilot elsewhere proves foot traffic spikes. The result is a cautious, incremental adoption curve that lags behind artistic innovation.

Community Engagement: Mandate Without Map

Responding to public pressure for inclusivity, RFPs now flag “community engagement” as essential. Yet definitions vary wildly: a single workshop, a co‑creation model, a survey? Budgets rarely climb in parallel, leaving artists to absorb unpaid facilitation labor. Worse, vague expectations invite post‑selection scope creep—an artist hired for a sculpture finds herself leading neighborhood history tours.

When engagement is undefined, it becomes performative. Panels award points for a paragraph promising “interactive listening sessions,” but success metrics disappear after installation. Communities notice the gap, and trust erodes.

Developer-Led Art: Branding First, Art Second

Oaklianna Caraballo at the Hyatt Place Gainesville during the FAPAP Conference, 2024

Private developers wield growing influence, commissioning headline pieces to differentiate properties. Their timelines are governed by construction schedules; their risk tolerance is governed by financiers. Curators hired on retainer may champion adventurous work, but branding consultants often exert veto power—no political themes, no dark palettes, nothing that might jeopardize leasing rates.

While these projects can supply generous budgets and streamlined decision-making, they can also compress artistic inquiry into a marketing deliverable. A neon sculpture might brighten a lobby but speak little to the social fabric outside its glass walls. Communities encounter the work as decoration, not dialogue.

Models That Work: Structured Guidance and Temporary Labs

The picture is not uniformly bleak. MTA Arts & Design in New York publishes clear milestones, mentors newcomers, and pays design fees at each phase—lowering speculative labor. Festivals like BLINK Cincinnati treat streets as laboratories, pairing emerging technologists with fabricators under tight but transparent production schedules. Artists test daring ideas at 1:1 scale; cities gauge public art planning before commissioning permanent iterations.

The City of Tampa provides a strong counter‑example to static juries. For every project, staff assemble a fresh panel that mixes an architect or project‑design representative, a professional artist or curator, and a neighbourhood voice; Public Art Committee members remain present only as non‑voting chairs. The ordinance further instructs the committee to “invite professionals in the visual arts and design fields” and to guarantee “appropriate community participation.” By rotating expertise and locality, Tampa reduces the probability that a single aesthetic preference hardens into policy.

The University of Florida’s Art‑in‑State‑Buildings (ASB) Program mandates a blind first‑round image review for every project, shielding jurors from artist identities until concept discussions begin. Florida’s statewide ASB handbook repeats the rule: “The first artist review shall be held as a ‘blind review’ to ensure fairness.” Blinding cannot erase all bias, but it demonstrably widens short‑lists, especially for emerging and BIPOC applicants.

Key to these successes is process clarity in the artist selection process. Artists know what documentation is required, jurors follow rubricized scoring, and the public sees prototypes evolve in real time. Transparency breeds both trust and experimentation.

The Gainesville Dialogue: Government Meets Private Innovation

At the 2024 Florida Association of Public Art Professionals (FAPAP) conference in Gainesville, a packed session spotlighted the growing friction—and opportunity—between government process and private innovation. On one side sat Oaklianna Caraballo, then FAPAP President and Public Art Specialist for the University of Florida. On the other, Iryna Kanishcheva, founder of Monochronicle, a tech-forward public art consultancy.

“We’re opposites in the best way,” Caraballo joked. “I represent a government program established in 1979. You’re a private business with the freedom to innovate. Together, we can identify real issues and help move this field toward a more equitable, artistically meaningful future.”

Their exchange covered everything from the effectiveness of resumes to the need for artist selection software that can verify credentials, reduce bias, and adapt to new media. “Do we really need resumes?” Kanishcheva asked. “Most artists are just firefighting their way through 70 open calls using the same PDF template.”

Caraballo noted that while her team does review supporting documents, they prioritize the work itself. Still, the documents offer important insight into an artist’s intent and process—especially in academic or institutionally driven projects. “Even for those of us with an art history background, it’s almost impossible to keep up with all public art artists,” she said. “An AI tool that summarizes bios and finds relevant online information—accurate, short, unbiased—could really help boards make better decisions.”

She also highlighted a recurring issue in application review: artists listing completed public art projects in their resumes but submitting unrelated or unverified images. “Sometimes the photos don’t match the claims. I’d love for AI to flag those discrepancies—show me if the work really exists where they say it does.”

Iryna Kanishcheva and Oaklianna Caraballo at FAPAP 2024, Gainesville, FL

Kanishcheva agreed that tech could support both sides of the process. She described Monochronicle’s hybrid approach: open calls paired with direct invitations, and a new Request for Ideas (RFI) model that prioritizes creativity over resume length. Kanishcheva noted that technology could play a pivotal role in improving the public art process for both administrators and artists. She emphasized that while creative evaluation still requires a human touch, machines can reliably handle early-stage tasks—like automatically filtering submissions based on eligibility, location, or other preset criteria. “Instead of manually scanning hundreds of entries for basic requirements, we can trust technology to do that instantly and accurately,” she said, highlighting the potential for streamlined workflows and faster decision-making.

They also discussed the value of blind reviews versus open deliberation, the need for fair rubrics, and challenges posed by inconsistent application systems. “Some artists are disqualified just because they forgot to upload files in a specific format,” Kanishcheva said. “Procurement shouldn’t override creativity.”

Caraballo acknowledged the burden: “I’ve spent hours trying to improve our public art process and the prompts we give artists, but I keep running into the same roadblocks. These are big questions—important ones—and they don’t have easy answers.”

Audience members echoed the need for better systems, including clearer RFQs, paid committees and concept phases, and streamlined applications that reduce both administrative and artistic fatigue.

As the session closed, it was clear that both public agencies and private platforms share a common goal: to evolve the selection process in a way that honors creativity, increases access, and ensures the best possible outcomes for communities.

Save the Date: FAPAP 2025 – Tampa, FL

The Florida Association of Public Art Professionals (FAPAP) returns for its 2025 Annual Conference, held May 14–16 in downtown Tampa. This year’s theme, “Cultural Resilience,” invites public art professionals from across the state and beyond to examine how our field adapts and endures—through shifting policies, funding structures, technologies, and community needs. The conference aims to foster connection, share best practices, and spotlight work that uplifts Florida’s diverse cultural landscape.

Among the featured sessions is a presentation by Iryna Kanishcheva, founder of Monochronicle, titled “Unlocking Public Art Potential with AI: Practical Applications.” Scheduled for Thursday, May 15, from 1:30 to 2:30 pm at the Hyatt Place, this talk will explore how artificial intelligence can be harnessed to remove bottlenecks in artist selection, grant writing, and project management. Iryna will demonstrate how tools like algorithmic screening, language models, and computer vision can streamline complex workflows and reduce bias—offering new efficiencies for both public agencies and private practitioners.

Join us in Tampa for three days of insight, inspiration, and actionable strategies to move public art forward. For details, visit: floridapublicart.org/conference

References

-

City of Tampa. Public Art Program – Panel Composition Guidelines. Tampa.gov.

-

City of Tampa. Public Art Ordinance, Sec. 4-30. Tampa.gov.

-

Florida Department of State. Art in State Buildings Handbook. fldoswebumbracoprod.blob.core.windows.net.

-

Florida Association of Public Art Professionals. FAPAP 2024 Conference Program – Gainesville. Floridapublicart.org.

-

The Art Newspaper. “Artists Paid Less Than £3 an Hour for Public Art Commissions.” The Art Newspaper, May 16, 2023.

-

Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). Call for Artists – Penn Station Access. Mta.info.

-

Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). Call for Artists – 8 Av Line. Mta.info.

-

Project for Public Spaces. “Funding Sources for Public Art.” Project for Public Spaces, May 1, 2024. https://www.pps.org/article/artfunding

-

Grantmakers in the Arts. Public Funding for the Arts 2023. January 22, 2024. https://reader.giarts.org/read/public-funding-for-the-arts-2023

-

Americans for the Arts. “Arts Facts: Source of Revenue for Nonprofit Arts Organizations.” Americans for the Arts, 2017. https://www.americansforthearts.org/by-program/reports-and-data/legislation-policy/naappd/sources-of-revenue-for-nonprofit-arts-cultural-organizations

-

The Independent Florida Alligator. “DeSantis Vetoes All State Arts and Culture Funding.” The Independent Florida Alligator, July 2024. https://www.alligator.org/article/2024/07/desantis-vetoes-state-arts-funding

-

The Washington Post. “Trump Proposes Eliminating the NEA and NEH as Arts Grants Are Canceled.” The Washington Post, May 3, 2025.

-

Maine Public. “Collins Criticizes Trump’s FY26 Budget Blueprint.” Maine Public, May 2, 2025.

-

National Endowment for the Humanities. “Grant Opportunity: National Garden of American Heroes—Statues.” NEH, April 24, 2025.

-

City of Stuart Community Redevelopment Agency. Incentive Programs Brochure. Stuartfl.gov.

Submitted by J Muzacz Artist, Mosaic & Murals - Post Author

When people ask how I get gigs and I tell them dozens of rejections and countless hours spent “gambling” on these art calls, I am not sure emerging public artists realize the struggle.

It’s such a horrible waste of so many artists’ creative time and energy. And thus I’m vehemently opposed to unpaid RFPs especially, considering that concepts and designs, budgets, etc. take so much more time and effort to produce, only to get an informal rejection with no helpful feedback whatsoever.

I’ve been lucky/hard working enough after making art for 20 years to have the luxury of an assistant who can now help with this type of admin, and still it comes at a huge monetary cost regardless if we win calls or not. Private commercial commissions are so much easier and more refreshingly quick and simple start to finish, without endless meetings and paperwork.

I’ve also been a volunteer panelist for Austin’s AIPP over 5 years, and seen the good and bad sides of a bogged down bureaucratic city entity beholden to certain guidelines and restrictions, which waters down projects to a digestible, apolitical level..

Nonetheless, we have to play so many games to survive as artists in this day and age, it is thankfully but one outlet for my own creativity. I’ve enjoyed crowdfunding and seeking alternative sponsorships and support for grassroots public art initiatives here in Austin, and will continue to build these alternatives by way of passion and collaboration towards contributing meaningful art in public spaces.

Thoughts by Mia Pearlman, Hot Topics in Public Art - Post Author

Kanishcheva and Caraballo clearly lay out the many frustrations artists and administrators feel about the RFQ process—why are we writing different versions of the same letter for each call? It’s maddening. If high school students can apply to 1,000 colleges with a common app, why can’t we standardize RFQs?